Author’s write-up for 🤪onelinecrypto

This is the official write-up for the crypto challenge 🤪onelinecrypto from SEETF23, written by yours truly.

The entire challenge (yes it’s a one-liner)

1

assert __import__('re').fullmatch(r'SEE{\w{23}}',flag:=input()) and not int.from_bytes(flag.encode(),'big')%13**37

Basically, the challenge is to compute a flag with 23 characters inside the flag format, such that its long_to_bytes value is a multiple of $13^{37}$. It actually turns out (unintendedly) that this line allows the use of unicode \w characters, but fortunately the SEETF rules overrides this by saying that the flag must be ASCII (e.g. SEE{අඣයලᘒᘑᘼᘇᘲᘹᘠᘄᘞᘣᘠᘬᘭᘕᘛᘭᘓᘑᘶ} passes the assert but is not SEETF-valid).

Quick history behind the challenge

Unlike my other challenges which were thought up / collected / refined over the course of the year, this challenge was only written a week or two before SEETF started. It all started seemingly innocently, when we were doing a crypto challenge on some CTF, and had successfully decrypted the message m, but could not get a meaningful flag out of it.

Complaints were plentiful on the CTF discord, but the direct inspiration came from the following offhand comment by fellow SEETF author Warri:

(It turns out that the challenge itself was broken, so it’s not a very interesting story.)

Nevertheless, my first instinct was to turn this into a crypto challenge: given the value of the flag modulo $n$, can you recover the original flag?

Now, I could have written it in a way that mirrors the original context (e.g. solve some RSA problem to get the plaintext mod $n$, then have the user solve for the bigger flag). But that’s not really my style – I like to have a challenge focus on a single thing, so that’s what I did.

So my challenge was quite literally somewhere along the lines of

1

2

3

4

5

6

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes

import os

flag = os.environ.get('FLAG', 'SEE{not_the_real_flag}').encode()

n = 2**255 - 19 # or some other random number I can provide outright

print(long_to_bytes(flag) % n)

It turns out my original choice of $n = 2^{255}-19$ was not a good idea, for reasons I will not explain in case I manage to turn it into a different challenge. But $n=13^{37}$ worked well.

It was while I was trying to decide what the flag should be that I thought: instead of having the flag be fun, why not have the output be fun? Something like… maybe, I don’t know… 0? That was when I knew it had to be a one-liner, and the final version of the challenge was born.

Intended solution, with explanations

It turns out that this challenge looked approachable to quite a number of people who had never heard of lattices before, only for them to go “huh?” when seeing the intended solution, as they were basically expecting it to be some optimised form of brute force.

So I’m hoping to do this writeup for them as a gentle introduction to lattices and stuff. And basically to prove that solving with lattices is really just an optimised form of brute force.

Brute Forcing

How would the most naive brute force work? We could just try all $63^{23} \approx 2^{137}$ flags (63 being the number of characters matching \w), but this is clearly too huge to brute force.

The other way probably makes more sense, which is to start with the smallest possible “flag” (that may not be made up of \w characters) that is a multiple of $13^{37}$, and then keep adding $13^{37}\times 256$ until we find a \w-matching flag. This gives us a complexity of $256^{23}/13^{37}\approx 2^{47}$ which does seem a lot more tractable (though still huge)!

So… what is the smallest possible non-\w flag? It is, of course:

1

b'SEE{\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x01\x0f^\x8b\xa8\xc6\xa6\x15n\x01\x9f\xe6\x1cn\x96\x10\n4}'

which is left an exercise to the reader, but we can write this solution as $x_1 = 52, x_2 = 10, x_3 = 16, \ldots x_{23} = 0$, or more concisely $\textbf{x} = (52, 10, 16, \ldots, 0)$. We opt to go right-to-left, and 52, 10, 16 are just the values of 4, \n, \x10 and so on.

How does adding relate to vectors?

What happens if we add $13^{37}\times 256$ to our vector $x$?

- Roughly speaking, we add this value to the first coordinate (i.e. add $\textbf{v}_1 = (13^{37}, 0, \ldots, 0)$).

- Then we keep subtracting 256 from the first coordinate and carrying the 1 to the second coordinate until the first coordinate is between 0 and 255 (i.e. add some multiple of $\textbf{v}_2 = (-256, 1, 0, \ldots, 0)$).

- Then carry from second to third (i.e. add multiple of $\textbf{v}_3 = (0, -256, 1, 0, \ldots, 0)$), and so on, until we reach $\textbf{v}_{23} = (0, \ldots, 0, -256, 1)$.

In other words, every vector in our brute force can be represented as

\[\textbf{x} + \sum_{i=1}^{23} a_i \textbf{v}_i\]for some integers $a_i$. And this is where lattices come in.

Lattices and stuff

See this term: $\sum_{i=1}^{23} a_i \textbf{v}_i$? That’s a lattice, where we have used the $\textbf{v}_i$ as a basis. Now, we don’t actually like this basis because the vectors are huge and not very orthogonal to each other, so we want to find a different basis. And that’s lattice reduction in a nutshell.

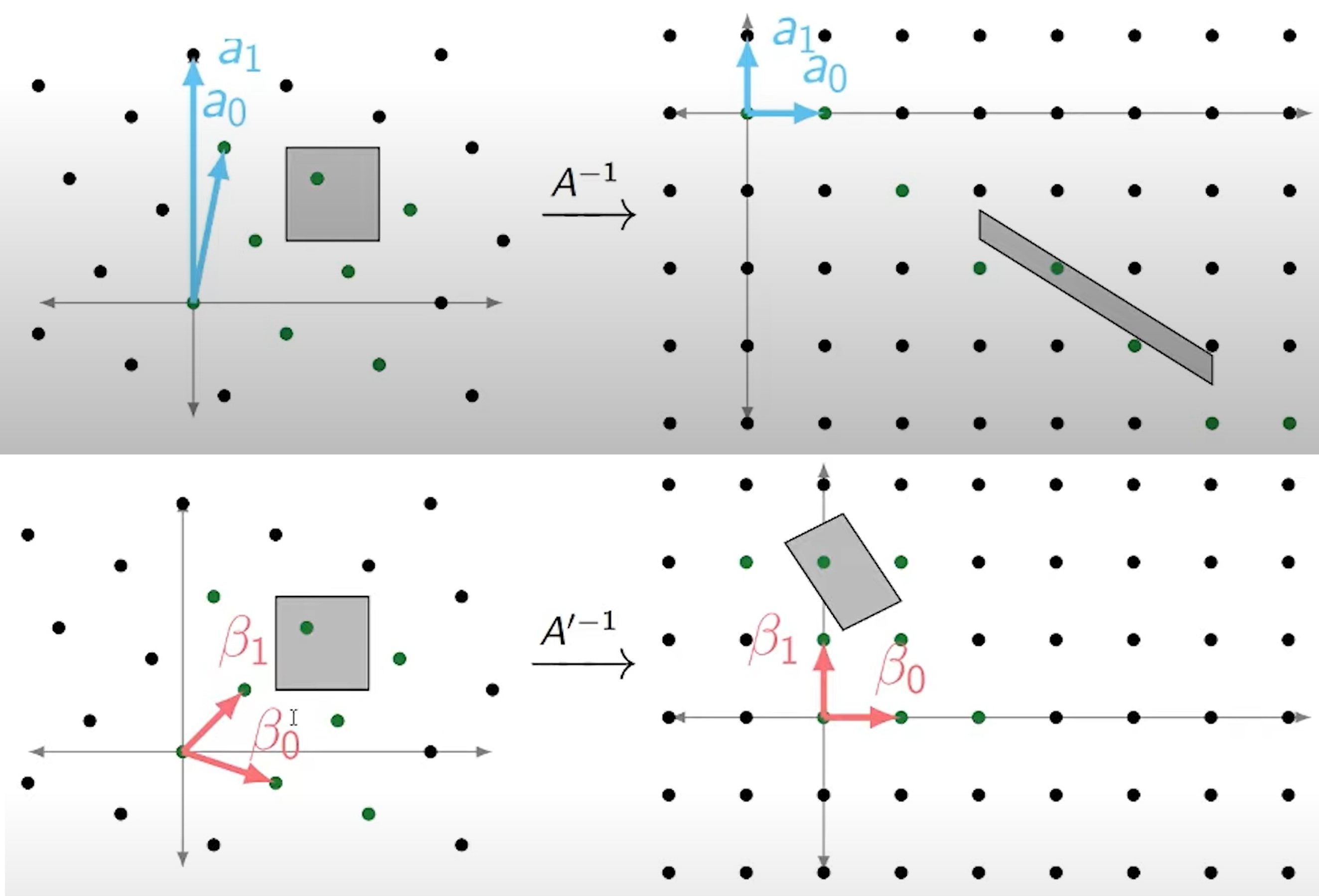

Here’s an image from wikipedia to demonstrate the concept:

Roughly speaking, a reduced basis means that we can get to all nearby points by adding only small multiples of our basis vectors.

Ok, so let’s actually reduce the lattice! We will use sagemath, which identifies lattices with the row span of a matrix. That means we can begin with the matrix

\[\begin{pmatrix} 13^{37} & 0 & 0 & \dots & 0 & 0 \\ -256 & 1 & 0 & \dots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -256 & 1 & \dots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & -256 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]And then run LLL on it to get a reduced lattice.

1

2

3

4

5

6

from sage.all import *

m = matrix(23, 23)

m[0,0] = 13**37

for i in range(22):

m[i+1,i:i+2] = [[-256, 1]]

print(m.LLL())

We get the following reduced matrix:

\[\tiny\left(\begin{array}{rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr} 19 & 19 & -24 & 19 & -2 & 24 & 9 & 15 & 10 & -24 & -32 & -15 & -22 & -10 & 6 & -17 & -2 & -6 & 10 & 0 & -6 & -9 & 0 \\ 0 & 19 & 19 & -24 & 19 & -2 & 24 & 9 & 15 & 10 & -24 & -32 & -15 & -22 & -10 & 6 & -17 & -2 & -6 & 10 & 0 & -6 & -9 \\ 17 & -10 & -5 & 2 & -4 & -2 & -9 & -16 & 8 & 1 & -16 & -23 & 4 & 31 & -49 & 3 & -10 & 14 & 4 & 13 & 15 & -31 & 1 \\ -5 & 23 & 18 & -3 & -8 & -50 & -11 & 3 & 27 & 7 & -4 & -3 & 9 & 27 & -21 & 11 & 1 & 19 & 5 & 2 & -25 & -13 & 24 \\ -1 & -7 & 23 & 21 & 6 & -36 & -19 & 6 & 6 & -30 & 18 & 21 & 8 & 17 & -32 & 16 & -4 & -5 & -10 & -34 & 2 & -13 & 24 \\ -11 & -18 & -21 & -32 & 15 & 5 & 20 & -3 & -13 & -2 & -17 & -32 & 10 & 14 & -5 & 8 & -31 & 10 & 14 & -6 & -4 & 20 & -28 \\ -25 & -17 & 58 & -2 & -15 & -2 & -29 & 7 & 4 & 17 & -6 & -23 & -20 & -4 & -4 & 17 & 12 & 0 & -19 & 12 & 14 & 5 & 16 \\ -2 & -16 & 0 & 3 & 22 & 29 & -26 & 3 & -15 & 2 & -37 & -28 & 16 & 15 & 1 & -39 & -22 & -5 & 1 & 27 & 11 & -6 & 3 \\ 0 & -4 & 30 & -5 & -24 & -14 & -14 & 8 & -3 & 21 & 37 & -22 & -24 & 1 & 10 & 11 & -5 & 5 & 24 & 15 & 36 & -27 & 0 \\ 39 & 24 & -20 & -5 & 5 & 59 & 23 & -5 & 6 & 2 & 12 & -18 & 2 & -11 & -7 & 4 & -12 & 23 & -20 & 3 & -31 & 17 & -24 \\ 15 & 3 & 35 & 10 & -19 & -2 & 3 & 27 & 9 & 9 & 12 & -50 & -3 & -12 & 22 & 5 & 6 & -14 & -5 & -27 & -36 & -3 & -6 \\ -1 & -4 & 2 & -8 & 7 & -14 & -18 & -11 & 6 & 12 & 16 & -11 & -20 & -16 & -20 & -10 & -37 & -20 & -11 & 14 & 56 & 7 & 31 \\ 1 & 0 & 15 & 8 & -23 & -6 & -12 & 10 & 28 & 4 & 33 & -10 & -17 & -10 & 20 & -2 & -30 & -30 & -23 & 9 & -25 & -20 & 6 \\ -23 & 2 & -46 & 15 & -18 & -4 & 11 & -13 & 48 & -32 & 11 & -12 & -7 & -8 & 1 & -7 & 14 & -13 & 7 & -34 & -40 & 8 & 9 \\ -13 & -9 & -11 & -6 & 2 & 1 & -46 & 6 & -15 & 6 & 5 & -25 & -7 & 30 & -4 & -5 & -28 & -52 & 0 & -15 & 15 & -29 & 10 \\ -16 & 15 & 13 & 1 & -20 & -3 & 7 & 0 & 8 & 3 & -6 & 9 & -50 & 1 & -8 & -8 & 1 & -25 & 17 & -47 & 18 & 6 & 29 \\ -11 & 12 & 23 & 20 & -32 & -18 & -11 & -23 & 19 & 1 & 24 & -52 & -15 & -19 & -20 & 17 & -14 & -5 & -13 & 1 & 17 & -33 & -23 \\ 0 & 0 & 4 & -30 & 5 & 24 & 14 & 14 & -8 & 3 & -21 & -37 & 22 & 24 & -1 & -10 & -11 & 5 & -5 & -24 & -15 & -36 & 27 \\ -21 & -13 & -41 & 13 & 38 & 8 & 6 & 16 & 16 & 17 & -12 & -17 & 2 & 16 & 31 & -23 & 6 & -17 & 15 & 6 & 3 & 26 & -9 \\ -1 & 3 & -5 & -22 & -23 & -23 & 27 & 40 & 14 & -8 & 10 & 9 & -26 & -19 & -38 & 9 & -19 & -10 & -20 & 3 & 3 & 6 & 14 \\ -33 & -13 & 46 & -26 & 13 & -9 & -24 & -14 & 6 & -18 & 0 & 11 & -7 & -14 & 48 & -23 & 0 & -20 & -16 & 5 & 33 & -15 & -32 \\ 13 & 8 & -1 & 23 & 38 & 0 & 15 & 3 & -32 & -21 & 43 & 18 & -21 & 8 & 30 & 1 & 13 & -34 & -12 & 22 & -11 & -3 & -19 \\ 3 & -36 & 3 & 23 & 23 & 6 & -10 & 3 & -17 & 10 & -12 & 21 & -24 & -37 & 20 & -25 & -1 & 26 & 10 & -36 & -9 & 25 & 13 \end{array}\right)\]Now, this basis looks like it’s more complicated than the original, but for all mathematical purposes it’s simpler. Let’s call the row vectors of this basis $\textbf{w}_1, \ldots, \textbf{w}_{23}$.

Where are we going with this?

So our aim has not changed: we still want to find all values of

\[\textbf{x} + \sum_{i=1}^{23} b_i \textbf{w}_i \textrm{ (note the new basis)}\]in which every coordinate satisfies \w. This is actually tricky to model directly, so we’ll loosen the requirement a bit and only require the coordinates to be between 48 and 112 inclusive. This range includes all \w characters, but also a bunch of other unwanted symbols.

Anyway, the picture here is that the region which we want is a hypercube, but if the basis is bad it gets sheared into something that spans a large possible number of values on each axis.

Here’s a picture for example (stolen from another presentation which I reference below, so the notation might not make sense):

The lower image is the reduced basis, and as you can see the projection of the region to either axis is smaller than it was with the original basis. This is basically the key to faster brute-forcing.

Linear programming, and branch-and-bound

Now that we have the reduced basis, we are ready to do a faster brute force! Recall our formula for all flags

\[\textbf{x} + \sum_{i=1}^{23} b_i \textbf{w}_i\]except that we can now work out e.g. the absolute minimum and maximum possible values of $b_1$. We can think of this as the endpoints of the sheared region as in the above image. This can be solved via linear programming (e.g. simplex method) very quickly, but is beyond the scope of this writeup.

Anyway, let’s say we compute the endpoints to be $-3.14 \leq b_1 \leq 2.718$. Then we can basically say that $b_1 \in \{-3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2\}$. This is the essence of branching: we try each of these cases separately. For each case, we have a smaller region, which we then iterate on the remaining $b_i$ to get new smaller bounds. Then at the end of the day we will have iterated over every point in this region.

Now to actually write code

Ok, so it actually turns out that there are lots of good frameworks that can help us with all of the above. We will use sagemath for LLL, and cpmpy for linear programming. But hopefully it is clear how each part of the code maps to what’s happening above.

Oh, and a couple of caveats:

1) Instead of starting from the “smallest possible flag” as we did above, I start from the illegal value (negative of SEE{<empty23>}, 0, 0, ... 0). This works because, well, once you add that to the flag you get zero. I place this into a new extra dimension of the lattice with a very large weight, to basically ensure that this weight doesn’t propagate into the other vectors. You don’t have to do any of this if you don’t like it, but I like it.

2) We will print all flags whose coordinates are between 48 and 112, but remember the final goal is to find \w-matching flags. We expect roughly $75^{23}/13^{37} \approx 81.4$ solutions of the former type, and only $63^{23}/13^{37} \approx 1.48$ of the latter.

Here’s the code!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

from sage.all import *

from cpmpy import *

import re

n = 13**37

empty = b'SEE{' + bytes(23) + b'}'

target = int.from_bytes(empty, 'big') * pow(256, -1, n)

m = matrix(24, 24)

m[0,0] = n

for i in range(22):

m[i+1,i:i+2] = [[-256, 1]]

m[-1,0] = -target

m[-1,-1] = 2**256 # some arbitrarily large number

def disp():

flag = bytes(x.value())[-8::-8].decode()

print(flag, '<--- WIN' if re.fullmatch(r'\w+', flag) else '')

x = cpm_array(list(intvar(-99999, 99999, 23)) + [1]) @ m.LLL()[:,:-1]

Model([x >= 48, x <= 122]).solveAll(display=disp)

The output order might vary depending on randomness, but here’s what I got when I ran it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

[ajlf?XbkTHTd:zfU6BI\sV

i[pUtgMLNN4RHEqYB:UbZEj

>sn9w`;\p@:5w9`F<15lN6C

Qr[vYvVKuCP_BkUK30Bjnha

7fxfWvajX8;g[cQ5OC0lWWy

^1tr@k2YURCj[a\2NW1LGTk

m>yVEU4RTsMnaTrHA;]n5@U

PNo>]hHxvw7;EQt0@P\rG=G

aOn2WeXYVq[FLY_YP?apICc

SUhII=coswoHhNhfc;NWKqO

I\lTaj\Iv`S1:wYScc[[2Jd

EBly?`m6q8C^<^aj]d;x9fB

AIjQCeJNLWUS=>Zm^EPm;M6

]ov3[sJUUk2wpoHxpiK=SQE

2oTYCa4RKd2hOnx=XlmhS[X

J^sVWJ@NRo0zClrBA1hmgC1

It=FSyXpcMyEKyC]sMspBa4

4Yv9fJxdAI53]o1f6q?==nR

@fc1jHW8P?3UtyGWYn9>BtT

;Op]mJb<_Ic^nt9\;6HBIM=

8L_BvIvRd0=ksZRh^10R1pR

R49]QeU5v9oHuu\nkG42gVK

d2N2hxm6HJrXF;PymAORWb\

8T3sBi[7<?ulU^oHb;CW@P\

B7BdB5?28]nSZd`N4<EQ5GO

I68ad=jE8UIrp8=Ri8e1:ad

y3[rH;p=CzB=`lEQA9FH5hR

mpFgIa]0TkgFGG6a_8sDGR@

ciqc4at`3\>7ZP6R^IRDj0?

gQHd;crtEr;=VdWAkKk5u:_

Z7IE4FHZGdT0q7U<Y6zanJY

dCy^A`zsxy3Uck;Mz^tELNK

ul3B1EfPTw71o<;l6o@_7`V

sj]a3Y@YIx869<?@EF]hJSo

^0Km0AkBlEB;pW\9XUellce

Q7XrEPCI[^E[o0:od@qEgD7

;Gn<_n^[w?[_cD@>_lTD[22

f;5?8prYS5cr3BzEfAhNwr8

8U^Vsvh_i88rT0mBO:ErQ\@

P0:Z8e6OqM\e0BT_T^]Rt^X

g>WZGS2nM?_^0m2ioDhIs<D

36oI14Nvb7jG1S2I\Ec9:7\

\IZ00HAaCwxNFo324RQ:J?Y

tIo2O?j;gF]19mIB0^\EX\9

lNg:EcFFiQeRCI8\9VUdwJe

gWx>T@>j>d<wBTDa10kO_Nv

luQ5xmNUKgEEDO_c5LoJCum <--- WIN

PnLBhU94e;xV6N4012a6EyD

AmMjlvJ:yGdvHZQDP2Ql4yz

Odv`^EBZ^S4b0r>[DTe:HUw

XuT>[>RdYUCe[jd?F8U62DM

4y`G?LG7a74FG5tO6ND6;oA

SvAMeic4Ez5Pd6:jFQ\yobU

;JM>YVP?>EWRl@OlHeQe4qv

3:aPdiKLHWqxzE1w4HzItaA

SMds0vrjEal3^h]z2ioBS@2

_ZQk4tQ>TWjUurskUfiCXF4

=DovyHGsH3qy]01Ez3<HAvD

gq^qb06jEgGjjsZYncK2VV7

xrVycT6G0_Pm29jkxscc`[T

pSlnc31tJWK`m4sGS^iw7on

hfirgDztk@]Rwq]FXiZqaxu

`Izpn5cj:1;Rn0thuy\f?_Q

6`Hz:Z=0ax77SmD\ptqXFwA

xD=t:9J67>I:rALmsuvi9><

zG:@YjfS>:h;b\m?coQe?C2

5BHKQAzdLE9\8dgC^oVKALo

4r:sX<zOj88y4isK4DcgT]W

U:VfRfT_6cCsV\kG5gnJVgn

KX>Yur?8;hhpC:\yi8^F1:n

[I2X\@65=14zb]^wuh:tDXQ

t;Y1xr8BKttSYO[Qd<k3<Cp

9nIM_j0lw]V]CXT:LExSiBz

2aQEzhqKwC?`<2Pa_zVmF2p

Uvc[c7c_sieQlTSv\^U1i6s

DsthC;T`?aqeS7`<\\`@?CY

CQz_NUBq_QpY9^w4>l4HjYz

H;yYm0cDOl\m\X^HeYX>neY

The flag is SEE{luQ5xmNUKgEEDO_c5LoJCum}.

Further reading

I highly recommend Minecraft Seeding Ep. 2: Part 1 and Part 2. It solves a different problem from what we are doing, but it’s explained well with excellent diagrams.

Also do check out the CryptoHack lattice series (further down the page under “Lattices”).