Write-up for lance-hard?

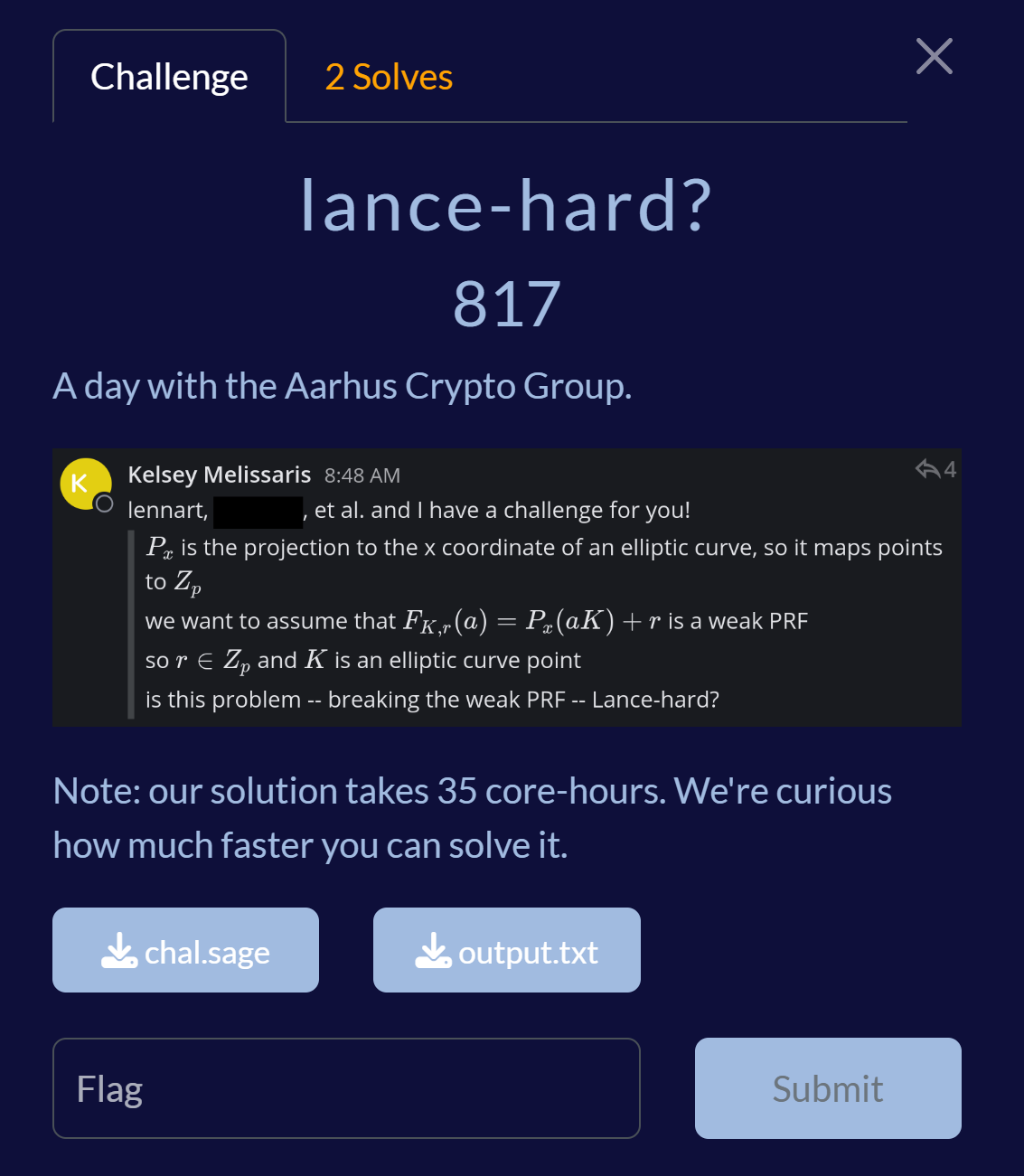

This is a write-up for an insanely difficult crypto challenge from KalmarCTF 2025 called lance-hard?. (Yes, the question mark is part of the challenge name.)

I hadn’t played CTFs in quite a while, but KalmarCTF always has great crypto challenges, and this year’s did not disappoint. I played KalmarCTF on the weekend of 8-10th March 2025 and despite spending almost all of it on this single crypto challenge, I think I learnt so much from it that I think it was well worth it.

Introduction

This was a challenge involving elliptic curves, and was definitely one of the hardest crypto challenges I’ve ever solved. The flavour-text certainly didn’t shy away from informing us that significant computation time might be required!

Challenge screenshot

Code for chal.sage

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

#!/usr/bin/env sage

from Crypto.PublicKey import ECC

from Crypto.Random import random as cryrand

from Crypto.Util.strxor import strxor

from hashlib import shake_128

samples = 1000

curve_bits = 80

p = (2^curve_bits).next_prime()

F = GF(p)

while True:

a = F(cryrand.randrange(int(p)))

b = F(cryrand.randrange(int(p)))

E = EllipticCurve(F, [a,b])

order = E.cardinality()

if order.is_prime():

break

print(p, a, b)

K = E.gens()[0] * cryrand.randrange(int(order))

r = cryrand.randrange(int(p))

for i in range(samples):

a = cryrand.randrange(int(order))

out = (a * K).x() + r

print(a, out)

with open('flag.txt', 'r') as flag:

flag = flag.read().strip().encode()

keystream = shake_128(str((K.x(), r)).encode()).digest(len(flag))

ctxt = strxor(keystream, flag)

print(ctxt.hex())

The challenge only had two solves by the end of the CTF, and congratulations to Sceleri on getting first blood!

This write-up will focus on how I solved it during the CTF, along with my train of thought on how I arrived there. The solve itself took about 5 hours of compute, and the exploration itself was quite the journey! After the CTF, I collaborated with Sceleri, and we came up a solve script that runs in under 2 minutes – but there’s so much stuff in there that I will defer this to a future post.

Solving the challenge

The setting behind this challenge is we have a known elliptic curve $E: y^2 = x^3+Ax+B$ over $GF(p)$, an unknown point $K$ on this curve, and an unknown $r \in GF(p)$. Let $q$ be the order of the curve. ($q$ is actually prime but this doesn’t really matter.)

We are given $n=1000$ samples of $P_x(a_i K) + r$ for some known, uniformly sampled $a_i \in \mathbb{Z}_q$.

The main important parameter here is $p \approx q \approx 2^{80}$, which determines just how much we can brute force.

Roughly speaking, this challenge splits into three parts that are somewhat independent of each other:

- Find a sparse relation between the $m_i$.

- Construct a polynomial in $GF(p)[X]$ that has root $r$ by definition.

- Compute the root $r$ of this polynomial.

Let’s dig in!

Part 1: Find sparse relation

First off, we’ll want to find a small, sparse vector $\mathbf{v} \in \mathbb{Z}^n$ such that $\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{v} = 0 \pmod{q}$.

The standard way of doing this is lattices (LLL+BKZ) and maybe lots of brute-forcing of different subsets of the $n$ samples. Best I managed to find this way was a vector with exactly 17 $\pm 1$s, and the rest $0$s.

How do we quantify how good a vector is? We want a vector that reduces the computation required in parts 2 and 3, so we can estimate this with an upper bound of the polynomial degree in part 2. We’ll handwave a bit and say that this upper bound is equal to $2^{\left|\mathbf{v}\right|_0-2}(\left|\mathbf{v}\right|_2^2-1).$

So we do want the number of non-zero elements to be small, since it’s a twofold increase for each one. But we also want the overall 2-norm to be small. So a bunch of $\pm1$s does sound like what we reasonably want. In particular, if there are exactly $w$ instances of $\pm1$ and zero elsewhere, then this upper bound is equal to $2^{w-2}(w-1)$.

Anyway $w=17$ gives us a polynomial of degree at most 524288, which seems reasonable, but we can do much better. Let’s see how we derive a $w=12$ solution using the generalised birthday problem.

Birthday problem!

Alright, this sounds like a classic MITM. Let’s first look at what we cannot do, and then work from there.

Classically, we can partition the 1000 $a_i$s into two halves, let’s say left and right, of 500 $a_i$s each. We can randomly take any subset of 6 $a_i$s on the left, apply any of the $2^6$ choice of signs, and add them. Which gives roughly speaking, a random value in $\mathbb{Z}_q$. The birthday problem states that we can find a collision by doing this $O(q^{1/2}) \approx O(2^{40})$ times on the left and right. Collision here means they are equal, so the difference is zero and we have 12 $a_i$s (up to sign) that sum to zero.

Technically this is a viable strategy, but my machine is not powerful enough to do $O(2^{40})$ in time or in space.

Generalised birthday problem!

Ok, hear me out, what if we partition it into 4 parts (of 250 $a_i$s each) instead, where we sample each part by taking a sum (up to signs) of 3 $a_i$s? Intuitively we can sample $O(q^{1/4}) \approx O(2^{20})$ items in each part, and then there should exist a set of choices that sum to zero. The maths does in fact work out, but it turns out we don’t know how to find this set of representatives.

Instead, Wagner says that with 4 parts we can do this in $O(q^{1/3}) \approx O(2^{27})$.

The paper is well worth reading, but I will sketch a rough high-level idea of the construction.

Sample $O(q^{1/3})$ items from the first two parts, let’s call these $S_1$ and $S_2$. We expect these to be roughly uniform across $\mathbb{Z}_q$. This means that if you pick an element $s$ of $S_1$, you can expect there to be roughly one element $S_2$ whose distance from $s$ is less than $O(q^{2/3})$.

Applying this over all elements in $S_1$ means we now have a new set $S_{1,2}$ of sums, whose elements are all less than $O(q^{2/3})$. And also $|S_{1,2}| = O(q^{1/3})$.

But now we do can the same thing on the latter two parts, so $S_{3,4}$ has the same properties. Finally, from the original birthday problem, we can expect there to be a collision between $S_{1,2}$ and $S_{3,4}$ and we are done.

One small problem

A crucial assumption in the above is that we can uniformly sample $O(q^{1/3})$ different items from the first 250 columns. Turns out we can’t do that, because if we take all triples, up to sign, there’s only $\binom{250}{3}2^3 \approx 2^{24.3} < 2^{27}$.

We work around this by just sampling $S_1$ and $S_2$ from the same left 500 $a_i$s. This gives us more samples to work with, but has the issue that a sum can be represented here more than once. For example, we might have $(a+b+c)+(d+e+f)=(a+b+d)+(c+e+f)$, and in fact each value appears around 10 times on average.

What does this mean for us? For starters, instead of finding differences up to $q^{2/3}$ we want differences up to $100 q^{2/3}$ instead. This allows us to sample $10 q^{1/3}$ items in each half, for a successful birthday attack.

Implementation

I wrote this part in C# (which is my main day-to-day language), but also it ended up kind of messy because the aim of the script kept changing, and I did many intermediate serialisations to disk and back. But the core idea is as follows:

- Calculate all $\binom{500}{3}\cdot2^3 \approx 2^{27.3}$ sums (for each half) into a list. Since signs don’t matter, I identify $x$ with $-x$, which means each element can be represented in $[0, q/2]$.

- Sort this list.

- Find all small differences (up to $\approx 100q^{1/3}$, though I specifically used a limit of $2^{60}$) of two elements in this list. Basically keep track of a start index and an end index. These small differences all fit in a 64-bit datatype.

- Birthday problem! Though the C#

HashSetwasn’t actually fast enough to pretend to have O(1) insertion at this scale, so since I had already serialised things to disk I just split them into 256 different files depending on the lower 8 bits, then ran 256 independent birthday attacks.

The process took around 1.5 hours. Partly because I serialised a lot of intermediate values to disk just in case. But anyway here’s some language-agnostic pseudocode to demonstrate the process.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

# left half

arr = []

for a,b,c in subsets(ais[:500]):

arr += [a+b+c, a+b-c, a-b+c, a-b-c]

reduce each element in arr to the interval [0, q/2]

filter out duplicates

sort arr

# arr has size 2^27, each element < 2^80

S12 = {}

for i in range(0, len(arr)):

for j in range(i+1, len(arr)):

if arr[j]-arr[i] < 2^60:

S12.add(arr[j]-arr[i])

# S12 has size 2^27, each element < 2^60

# right half

same thing as above: construct S34

foreach s in the intersection of S12 and S34:

# we have a collision!

find s1 and s2 s.t. s1+s2 == s

find a,b,c s.t. a+b+c == s1

repeat for s2, s3, s4

we have a relation of 12 ais, so print it

Anyway, the birthday attack says there’s a 50% chance it’ll print something. And it managed to spit out a single solution:

1

[(39, 1), (70, -1), (98, -1), (173, -1), (404, -1), (653, 1), (760, 1), (818, -1), (847, -1), (893, -1), (918, 1), (964, 1)]

which was good, otherwise I would have given up on this challenge.

Part 2: Construct a polynomial

The plan in this part is to use $x$-only equations. This seemed the most immediately intuitive idea to me, so I was kind of surprised to find that everyone else used $y$-coordinates as well and then eliminate those at the end.

So what do I mean by $x$-only equations?

Proposition: If three points on an elliptic curve add to zero, i.e. $P+Q+R=0$, and their $x$ coordinates are given by $x_P$, $x_Q$, and $x_R$ respectively, then

\[(x_Px_Q+x_Px_R+x_Qx_R-A)^2 - 4(x_P+x_Q+x_R)(x_Px_Qx_R+B) = 0,\]where $A$ and $B$ are the parameters of the elliptic curve. [proof omitted]

Let’s denote the function on the LHS by $S_3(x_P, x_Q, x_R)$.

What if we had 4 elements $P+Q+R+S=0$ instead? Well, consider a temporary value $t$ which represents the $x$-coordinate of $P+Q$ (so it’s also the $x$-coordinate of $R+S$). Then $S_3(x_P,x_Q,t) = S_3(x_R,x_S,t)=0$.

And thus we can use the resultant to eliminate $t$! That means we can define

\[S_4(x_P,x_Q,x_R,x_S) = Res_{t}\left(S_3(x_P,x_Q,t), S_3(x_R,x_S,t)\right).\]This scales up the way you’d expect; just add an extra resultant for each new point.

Finally, let’s link this back to part 1. Remember our sparse relation? The relation basically just gives us 12 points adding to zero, i.e.

\[S_{12}(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{12}) = 0,\]and we now know exactly how to construct this!

Side note: I only found out after the CTF that this construction already has a name: Semaev’s summation polynomials.

Oh, but for this problem specifically, we don’t have actual $x$-values. Instead, we have $x$-values offseted by some unknown $r$. That means we have $S_{12}(g_1-r, g_2-r, \ldots, g_{12}-r) = 0$. The $g_i$ values here are given, so this is actually just a polynomial in $r$. Of degree at most 11264.

Anyway, here’s the rough code for this

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

p, a, b = 1208925819614629174706189, 73922274628233716557252, 512377843723837814597638

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve(F, [a, b])

def S(xs):

if len(xs) == 3:

return (xs[0]*xs[1]+xs[0]*xs[2]+xs[1]*xs[2]-a)^2 - 4*sum(xs)*(prod(xs)+b)

G.<t> = xs[0].parent()[]

return S([t] + xs[:len(xs)//2]).resultant(S([t] + xs[len(xs)//2:]))

gs = [190779513796414027986976, 1138174939847931790545901, ...] # givens of length 12

G.<r> = F[]

f = S([g-r for g in gs])

Now $f$ is just the desired polynomial, and we can move on to the next part. It took around 3 hours to compute this polynomial, which is largely because polynomials are really slow in sage. A couple of other people implemented their own polynomial class just to overcome this.

Speedup by using Lagrange interpolation

After the CTF, I played around with how to reduce this 3 hour calculation. It hit me that I could just calculate 11265 different values, then Lagrange interpolate after. That means the evaluation of $S_m$ itself will done without any polynomials, albeit many more times.

So we can do something like this:

1

2

ys = [S([g-r for g in gs]) for r in [0..11264]]

f = G.lagrange_polynomial([0..11264], ys)

But of course, lagrange_polynomial actually turns out to be slow at $O(n^2)$ so we can also use ProductTree to achieve the same thing in $O(n \log^2(n))$:

1

2

3

from sage.rings.generic import ProductTree

G.<r> = F[]

f = ProductTree(r-i for i in [0..11264]).interpolation(ys)

which completes in about 11 seconds.

Actually, we can still do better using the fact that we are interpolating over consecutive values of $x$, rather than arbitrary ones. I hope to discuss this in a future post.

Part 3: Solve the polynomial

Can we just evaluate f.roots() directly? At first sage complains with this mysterious error

1

2

PariError: the PARI stack overflows (current size: 1073741824; maximum size: 1073741824)

You can use pari.allocatemem() to change the stack size and try again

so I just threw 16GB of RAM at it: pari.allocatemem(16 << 30) and then it worked!

It still took about 10 minutes to compute the roots, but shows that it can be done. Which is good, because factorisation of polynomials in finite field is a solved problem.

Speedup by using GCD

If we had two polynomials with the same root $r$, we can just GCD them which is faster. So we could find another relation and construct another polynomial, but then again constructing the polynomial was the bottleneck in the first place!

I credit the following trick to soon_haari, who himself credits it to genni. And also Blupper for simplifying it in sage.

Basically $g(x) = x^p-x$ is the product of all linear factors $x-i$. This gives us a polynomial with root $r$ (indeed, every root)!

So now the code is just:

1

2

g = pow(r, p, f) - r

print(f.gcd(g).roots())

which completes in about half a second.

Conclusion

Wait, where’s the flag?

I mean we’re all here for the maths right? But here it is anyway.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

from pwn import xor

from hashlib import shake_128

p, a, b = 1208925819614629174706189, 73922274628233716557252, 512377843723837814597638

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve(F, [a, b])

q = E.order()

a1, x1 = 249997655098690656297225, 801261023538607792690339

r = 221571505269605005502902

K = E.lift_x(x1 - r) / mod(a1, q)

ctxt = bytes.fromhex('9a38ebbdbbd7b1bfa50fa5284c3af2fb01ba95b1224b58bae3cb75637297a35a176330a1acddf697da62724a')

keystream = shake_128(str((K.x(), r)).encode()).digest(len(ctxt))

print(xor(keystream, ctxt))

# b'kalmar{sUB3xPoNEnTIAL-tiME-1SNT-Alw@yS_FAST}'

In conclusion, my solve uses about 5 hours of computation:

- 1.5 hours to find a 12-relation of the $a_i$s

- 3 hours to construct a polynomial with root $r$

- 10 minutes to actually solve the polynomial

After the CTF ended, I got it down to about 40 minutes:

- 40 minutes to find a 12-relation, using C++

- a few seconds to construct a polynomial (discussed above)

- under a second to solve the polynomial (discussed above)

But also Sceleri then one-upped me by solving it in just 15 minutes.

So of course we collaborated, and as a result we ended up with a solve script that completes in under 2 minutes. There is so much to discuss in that direction that does not fit in this write-up, but here’s a sneak peek of things you might look forward to in a future post:

- how to find an 11-relation of $\pm1$s

- how about a 10-relation? do they even exist?

- why hashmaps are so slow at $> 2^{30}$ elements, and what are the alternatives (e.g. bloom filter)

- sparser relations (8 or 9-subsets) with larger coefficients (not just $\pm1$)

- these are much easier to find (order of seconds)

- the polynomial degree grows from 11k to 300k

- $x$-only multiplication in elliptic curves

- why sage polynomials are so slow:

- why they’re fast if $p < 2^{63}$

- for large $p$, why

PolynomialRing(GF(p), implementation='generic')is sometimes faster than the non-generic - when/how to just Lagrange interpolate instead of using polynomials

- faster Lagrange interpolation when the $x$s are consecutive

- revisit the infamous flag_printer from picoctf-2023

- a closer look into Semaev’s summation polynomials, specifically a later paper by McGuire and Mueller discussing fast evaluation

- multithreading in sage, or really multiprocessing

- what is a Summoning Salt and why isn’t this a video write-up